Even though feminism has evolved past “bra-burning,” it’s still a heated term.

Mike Nicholson, founder of the Progressive Masculinity program, said that as soon as he mentions feminism in his youth workshops, “you can feel the shift in the room; they’re shuffling in their seats…A lot of it is bred from misunderstanding and how the word is smeared.”

I was curious what level of virtual seat-shuffling exists on LinkedIn, so I launched a poll asking the critical question, “Can men be feminist?”

Some people still think that men can’t be feminists

Of the 302 survey respondents, 87.7% believe that men can be feminist while 6.3% said they cannot. A brave 6% of respondents said they weren’t sure.

While a majority of folks agree that feminist is not limited to one gender, there’s still about 12% who firmly disagree or aren’t sure where they stand.

As Nicholson said, this might stem from historical stereotypes that feminism is a liberal-only ideology or that the word is a “smear” or insult. One survey respondent agreed, saying that “some men don’t feel they are welcome to step into the field of feminism.”

Another respondent described how, in his Hispanic culture, “the word feminism is taken in…poor taste because of how they identify it with the extremists on the left.”

There is still work to do in educating and empowering men that feminism is not a threat, but a way to improve the opportunity set for women—and as a mutual benefit, create space for men to live into their full potential.

As another respondent explained, “It takes everyone, not just women, to ensure equal treatment, equal pay, equal rights for women. When men in the workplace, in life, stand up for what’s right, it strengthens the human experience for everyone.”

(While this data is really interesting, it’s worth noting that most of my LinkedIn audience is likely to skew towards the affirmative answer. I’d expect numbers from the general population to show a larger percentage who believe that men can’t be feminist—meaning there’s even more work to do.)

Women are more likely to say men can be feminist

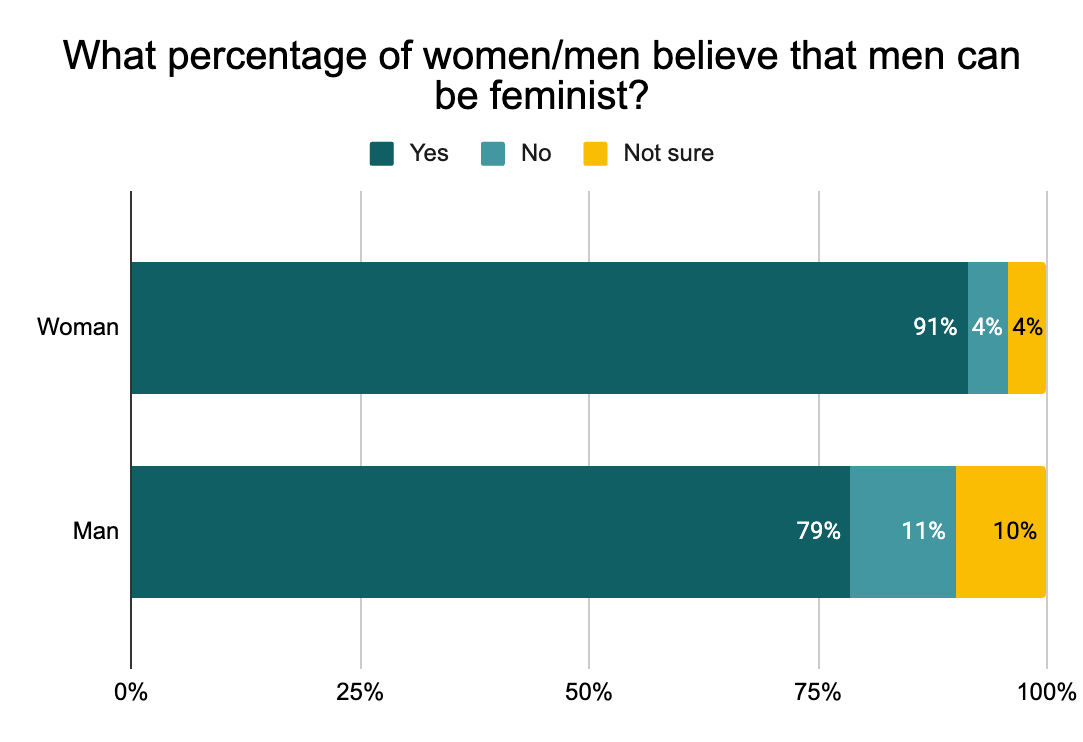

When I separated the responses by gender, women were more likely to believe that men can be feminist; 91% of female respondents answered “Yes” versus 79% of male respondents.

Men were also more likely to admit that they weren’t sure whether or not they could be feminist.

This data wasn’t particularly surprising to me—women know that we need male allies, but men aren’t always bought into the idea of male feminism—however, it was an important indicator as to where we need to focus our effort.

If we want to see gender equality improve in our workplaces, homes, and communities, we need men to engage in the work. We need men who are dissatisfied with the state of things. Men who ask for, listen to, and believe women’s stories. Men who don’t wince at phrases like “pay gap,” “parental leave,” or “me too.”

A recent paper in the “Academy of Management” journal supports these findings. Insiya Hussain found that when women and men raise their voices together, they get more buy-in from managers. Mixed-gender coalitions were 8% more successful in signaling that gender equity is an important issue for their organizations.

Men can support women by embracing feminism, women can support each other

If we want to see change in our organizations, we need men and women working together for gender equality.

One male respondent, reflected this mindset by sharing how he learned feminism from his mother: “You better believe I am in favor of supporting women’s rights to be treated with respect, dignity and equality in both social and professional settings.”

We also need to eliminate female rivalry in our organizations and ensure that our feminism is intersectional. As one female respondent said, “A number of white women who call themselves feminists don’t speak up for their Black, Asian, Indigenous, Arab and other sisters from the global majority.” We can all work to unpack our own privileges and make the future brighter and more inclusive for our daughters.

Further reading:

- Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace by David G. Smith and W. Brad Johnson

- White Women: Everything You Already Know About Your Own Racism and How to Do Better by Regina Jackson and Saira Rao

- Inclusion on Purpose: An Intersectional Approach to Creating a Culture of Belonging at Work by Ruchika Tulshyan